- Home

- Creativation by NAMTA

- Membership

- NAMTA Connect + The Studio

- About

- Resources

- Tariffs + The Creative Industry

- Cards for Congress Campaign

- CA Wildfires Relief: How to Help

- Creative Products Certification Program (CPC)

- Creative Outlook Market Research Study Report - MEMBERS ONLY

- The STUDIO Recordings - MEMBERS ONLY

- Membership Directory - MEMBERS ONLY

- Meet the Creative Professionals

- Meet the Independent Reps

- New Products

- Subscribe to Our Email List

- Discount Savings Programs

- Job Board

- Contact

- Advocacy

|

February 6, 2019 The Palette is available to all interested with an e-Subscription

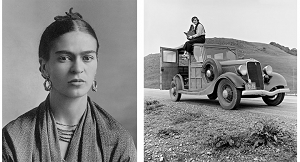

Frida Kahlo’s Friendship with Dorothea Lange Was Good for Her Health

Frida Kahlo’s Friendship with Dorothea Lange Was Good for Her Health

But even the most brilliantly embroidered floral skirts didn’t fool someone who shared a polio-effected childhood: the discerning documentary photographer, Dorothea Lange. Lange hid her own wizened right leg with wide leg trousers, not skirts, but recognized a shared gait when she first met Kahlo in November 1930. “[Kahlo] moved in a way that was all too familiar to me,” a fictional Lange narrates in Learning to See, a historical novel by Elise Hooper about the photographer’s life that will be released later this month by Harper Collins. “I watched her cross the marble floor, her long skirt pulling to the right with each step to reveal a slight limp.” The chance encounter between Lange and Kahlo took place when the Mexican twosome came to San Francisco so that Rivera could compete for mural commissions. One of Rivera’s competitors for the San Francisco Stock Exchange mural happened to be prominent Californian painter Maynard Dixon — Lange’s husband — but this didn’t prevent the two couples from socializing on a few occasions. Rivera was a star, and the whole city seemingly wanted to meet him. “As Rivera became the toast of San Francisco, the relationship between Kahlo and Lange strengthened,” says Elise Hooper, author of Learning to See. “Kahlo often painted in Lange’s studio to get some space from her husband’s active social life.” Rivera also gave Lange a few of his drawings of monumental laboring figures, which may have influenced her later Depression-era photographs, such as “Migrant Mother” (1936) — the image for which she is best known. “That Rivera combined artistic genius with passion for the oppressed and exploited was not lost on her,” writes Linda Gordon in her 2009 biography of the artist, Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits. But it was when Rivera began a very public affair with his model for the San Francisco Stock Exchange mural that the bond between Lange and Kahlo strengthened beyond their sisterhood of skinny right legs. The photographer’s husband also had a penchant for infidelity, and she, too, was in a marriage of two artists trying to advance their careers. “At this painful moment, Dorothea made a quick and intense connection with Frida: here was a disabled woman of great talent, charm, and political commitment, with a philandering artist husband. Like Dorothea, but twelve years younger,” Gordon writes. And so, in addition to giving Kahlo use of her studio as a means of creative escape, Lange granted the younger artist an enduring gift: an introduction to a man who would become her lifelong physician and trusted friend, respected thoracic surgeon Dr. Leo Eloesser. Eloesser was one of Lange’s clients, in addition to being culturally savvy and Spanish-speaking. Kahlo originally saw him because of the chronic pain in her right foot, an ailment for which he suggested rest and a healthy lifestyle (with far more moderate alcohol consumption). As Kahlo’s relationship with Eloesser developed and she shared her history — such as the serious bus accident she had survived at age 18 — he came to know her medical situation more fully. In gratitude, Kahlo gifted Eloesser a portrait during that first trip to San Francisco. One of her earliest works, she painted a full-length likeness of the doctor at his home at 2152 Leavenworth Street, standing next to a model ship called “Los Tres Amigos” (a reference to the friendship between Eloesser, Kahlo, and Rivera). Kahlo trusted Eloesser inherently, and kept in touch with him for the rest of her life. Two years after their first meeting, Kahlo wrote to the surgeon from Detroit for a second medical opinion; she was pregnant and wanted to know if her body could carry a child to term. “You have no idea how embarrassed I am to bother you with these questions,” Kahlo wrote, “but I see you not so much as my doctor as my best friend, and your opinion would help me more than you know.” (It is unknown what Eloesser said, but Kahlo kept the pregnancy and soon had a miscarriage that she documented in her 1932 painting, “Henry Ford Hospital.”) Their correspondence continued, with Kahlo addressing letters to her querido doctorcito (‘dear little doctor’) that included updates on procedures carried out by her Mexican doctors and occasional brags that she had given up drinking (“cocktailitos”), as per his recommendation. She wrote about non-medical maladies as well, and Eloesser was her confidant. “You have no idea what I suffer,” she once wrote to him. Around 1940, when Kahlo was devastated by her recent divorce from Rivera and in poor health, Eloesser urged her to come to San Francisco for treatment and counseled her to accept Rivera as he was, despite his faults. “[Rivera] has never been, nor ever will be, monogamous,” Eloesser wrote, “[but] Diego loves you very much, and you love him.” Eloesser encouraged her to accept him and remarry. A few months later she agreed, remarrying Rivera in a San Francisco courtroom in November 1940. Kahlo then thanked her friend with another painting, “Self Portrait Dedicated to Dr. Eloesser” (1940), with an inscription to “Doctor Leo Eloesser, my physician, my best friend. With all my love.” Lange’s referral proved invaluable to Kahlo, and ultimately also fruitful for the San Francisco General Hospital (where Eloesser worked for 36 years). Eloesser owned paintings by both Kahlo and Rivera, which have been displayed in the hospital lobby for 50 years. Eloesser gifted these works to a colleague and close friend, who in turn gave them to the hospital in 1968 with the stipulation that they be publicly viewable. For years, they hung high and barely visible in the lobby; as of a recent renovation completed in 2017, the works now hang prominently at eye level to the right of the guard station. “Never did a painter, man or woman, so successfully transfer his (or her) emotions to canvas,” Eloesser wrote of Kahlo in his journal. In turn, Eloesser transferred free access to one such canvas to the future patients of San Francisco, the city he and Dorothea Lange called home. Hyperallergic

How museums in Norfolk, Virigina, are acting to protect art in face of growing flood risk

While the city “has begun to invest in mitigation and adaptation actions”, the report says, “recent estimates indicate it will cost hundreds of millions of dollars to improve storm water pipes, flood walls, tide gates, and pumping stations”. For arts venues in the region, resiliency plans are no longer just a question of how to keep the floodwaters back, but also how to accommodate the regular arrival of water and create pathways for it to run quickly back into river or sea. The Chrysler Museum of Art, located on the bank of the Hague—an inlet off the Elizabeth River—completed renovations in 2014 that emptied the basement, moving the on-site collection well above sea level, and raised the ground floor galleries by 10ft. (The museum also stores objects at an offsite location.) Now its long-range plans include elevating the streets around the building and potentially acquiring more land to create a space that would help absorb run-off water. “It’s not so much that we’re worrying about the art,” says the museum’s director Erik Neil—he is confident the museum’s encyclopaedic, millennia-spanning collection is secure—“but if staff and visitors can’t get to the museum, then you have a problem. We have to make sure that the museum isn’t isolated.” At the Hermitage Museum & Gardens, located further north on the edge of the Lafayette River, plans are also under way to mitigate the effects of climate change. A $1.7m city-run wetlands project will restore marshland in the surrounding area that has been eroded, and the Hermitage’s Visual Arts School will undergo renovation over the next few years, including plans to accommodate “the water moving across the property and back into the river”, says Jen Duncan, the museum’s director. The museum building itself is located on the highest part of the property and Duncan says she has yet to see water crest the bulkhead, though it has come close. None of the buildings on the property can be raised or significantly altered due to their being historic and so subject to conservation guidelines. While institutions work to flood-proof their properties, they are also incurring increasing insurance costs, as well as incidentals from closure during hurricanes and storms. “There’s a steady increase in insurance year after year, which is unpleasant but it’s not such a dramatic increase that it’s making the situation intolerable,” Duncan says. Institutions say that, by and large, they are getting the support they need from local and federal governments, but scientists’ predictions suggest a future for the city that may require a more united and comprehensive strategy to protect the arts community (and the city as a whole). Scientists at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science have gamed out three different scenarios for sea-level rise in the region, and say a moderate estimate would see the ocean water climb by 4.5ft by 2100—with king tides and storms extending the flood area inland. More extreme predictions forecast a 6ft sea-level rise or more. This year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has recorded 14 days of high-tide flooding in Norfolk. William Sweet, a scientist at NOAA, says that he expects that figure to increase to between 50 and 75 days of high-tide flooding per year by 2050, and likely jump to between 250 and 325 days per year by 2100. “We’re all aware in Norfolk that by 2100 most of the city is going to be under water,” says Duncan. “We all know, long-term, that most of Norfolk is going to have to move elsewhere eventually. I think there is a large conversation here about the results of the most recent studies, but from what I see there has not yet been a major shift to a more comprehensive discussion about the reality of what our future’s going to look like.” At the Chrysler, Neil—who used to run what is now the Newcomb Art Museum in New Orleans and shepherded the institution through Hurricane Katrina—feels optimistic about the future of the institution, though he is realistic about the predicament they face. “We’re able to act now with reference to Katrina or Sandy,” he says. “People do see how devastating a flood could be. We’re a valuable asset and the city recognises that. But I suppose it’s true that if we don’t see real alleviation in the next decade then we’d have to give consideration to moving to a new spot.” The Art Newspaper

STUDY OF LEONARDO'S 1ST LANDSCAPE FINDS HE HAD 2ND THOUGHTS

The Galleries said the 1473 "Landscape Drawing for Santa Maria della Neve" was taken on Thursday to a Florence restoration laboratory for study, which began right away with microscopic examination. Aided by sophisticated, non-invasive instruments, such as infrared light, the experts on Thursday scrutinized the front of the drawing. Later they will study the back, where there is a sketch of a human figure, the prestigious Florence art museum said in a statement. Art historian Cecilia Frosinini, who is supervising the scientific study, said that initial examination showed that Leonardo worked in two different phases. "It's possible that Leonardo went back to the drawing in a second moment, maybe right after his studies of geology and rocks," she said. The drawing, dated Aug. 5, 1473, in the upper left corner, depicts a bucolic scene, with a castle on a hill in the background and a valley dominating the design's center. Leonardo is celebrated as a Renaissance genius who excelled as an artist and who had creative scientific curiosity as well. Some have hypothesized that the drawing depicted an actual place in Leonardo's native Tuscany, or as Uffizi director Eike Schmidt said, "was a kind of 'photograph' of this or that valley, of these or those mountains." But the discovery that Leonardo worked on the drawing in two distinct phases "tilts the scale toward interpretations that underline the imaginative aspect and the character of intellectual speculation by the artist," Schmidt said in a statement. The Uffizi only occasionally displays the work, Leonardo's earliest known drawing, because it is so fragile. But on April 15 it will go on display for five weeks in Vinci, the artist's hometown, as Italy marks the 500th anniversary of Leonardo's death. The landscape, done when he was 21, is Leonardo's earliest known dated drawing. Until recently, it had also long been considered his earliest known dated artwork. Then, in 2017, a painted terracotta tile was attributed to Leonardo. Painted when he was 19, it depicts the Archangel Gabriel and is dated 1471. WSB

Art Helps Cancer Patients Recover

The effort was renamed the Ernest H Rosenbaum, MD Art for Recovery after Dr. Rosenbaum died in 2010. Rosenbaum, a former UCSF oncologist and hematologist, helped build the comprehensive cancer care program at UCSF’s Mount Zion Hospital in the early-1970s. He conceived the idea of bringing expressive arts to cancer and HIV/AIDS patients. Roughly 200 patients participate in Art for Recovery’s once-a-week, three-hour Open Art Studios workshop. In- and outpatients can partake of Open Art Studio at the Bakar Cancer Hospital, which started sessions in 2015. Outpatients can engage in Open Art Studio at Mount Zion. According to Cynthia Perlis, who directs the program, the Mount Zion sessions are so full they’re standing room only. Inpatients can also participate in Art for Recovery from their hospital bed. Non-art activities include writing workshops and visits by musicians at Mount Zion and Mission Bay. Volunteer guitarists, harpists and madrigal singers also perform in hospital lobbies. “Our Art for Recovery music coordinator holds a Sing-A-Long a few times a month in the Mount Zion lobby; patients, staff, and caregivers…sing along to a musician playing recognizable songs,” said Perlis. According to Perlis, Art for Recovery allows adults coping with cancer to become part of a community where they find others living with similar issues. “The program inspires our patients and helps them express how they are feeling through the expressive arts,” said Perlis. Perlis has guided the program since its inception. Today, its staff includes an artist-in-residence, music coordinator, two harpists, a creative writer, and a writing workshop leader, as well as UCSF medical student volunteers. Participants range in age from 18 to 80. “We have a tremendous amount of art materials, including acrylic paints, pastels, colored pencils and markers. We are able to show our participants how to work with the art materials and offer prompts to help them express their feelings about illness. We also display participant artwork in two large glass cases in the lobby of the Bakar Cancer Hospital…throughout the clinics and inpatient units. The new UCSF Precision Cancer Medicine Building is set to open in the spring of 2019 (with) patient canvases in all 122 exam rooms and, in addition, work purchased from artists in the Bay Area community,” said Perlis. According to Perlis, even when they’re not feeling well, patients get out of bed to attend Open Art Studio. “The Art for Recovery workshops bring patients together where they may make a new friend who is also living with a life-threatening illness. These patients are humanity at its very best,” she said. Amy Van Cleve, Art for Recovery artist in residence, runs Open Art Studio sessions at Mission Bay and Mount Zion. “I first came to UCSF in 2004 with a dear friend battling cancer. I found the Art for Recovery program and volunteered while my friend was receiving treatment,” said Van Cleve. Van Cleve, who worked for six years as a muralist before joining UCSF, said being in a hospital can be frightening and isolating. “Art creates an opportunity to expressing what words cannot in the darkest of times. (I) ask people how they are doing. “What color do you like? What symbols have personal meaning to you? What have you always wanted to try artistically but, been afraid?” Then I listen. From what people tell me I am able to create simple, non-threatening projects that can be completed in a short amount of time, no skill required. I always remind people there is no grade for their work, try to keep it fun, and mostly about expressing wherever they are at,” said Van Cleve. Hideka Suzuki, an Art for Recovery participant, has been out of treatment for five years but still attends workshops in Mission Bay. “The program helps me be self-aware. I express joy, not just fear or stress. The workshops continue to help me get through the day to day,” said Suzuki. “I was diagnosed with cancer in 2009 and it came back in 2013. I have to go back for a scan. I’m very nervous. Art for Recovery helps me get through that.” Mary Isham, who is living with cancer, said before going to Art in Recovery she didn’t consider herself an artist. “I only did art with my kids. When I came to treatment, I saw the sign for Art for Recovery workshops and followed it. There I met Cindy (Cynthia Perlis). She gave me a little book and colored pencils and told me, “I want you to draw every day.” I did for about four years, and it was transformative. I did classes for seven years with Art for Recovery. It was a very tight and supportive group. Eventually I started identifying as an artist. Now I sell my artwork. I have been in art shows, including the Box Show in Gallery Route One in Point Reyes for the last 12 years,” said Isham. Isham’s primary art form is painting. “I use very bright colors. I use them all at once, like in a rainbow. I started out painting with my hands. This helped me feel like I was pushing out the cancer. I started with reds, yellows, and oranges, like there was a fire inside. I wanted to get out my grief, my fear, my sadness. Now I paint joy and light. Art shows me I have a life beyond cancer,” said Isham. Before being diagnosed with cancer, Isham had practiced adolescent medicine for 25 years with the San Francisco Department of Public Health. “I helped start a mental health and reproductive and family services clinic at Mission High School in the late-1980s. We provided everything from detox services to stress reduction classes for teachers. But when I was diagnosed 20 years ago, people wouldn’t even say the word “cancer.” Art for Recovery was my support group,” said Isham. Alex Withers, a UCSF medical student between her third and fourth year, has volunteered with Art for Recovery, conducting bedside sessions, for the past three and a half years. “I bring art supplies and work with individual patients who cannot leave their room or might be uncomfortable doing so. Sometimes we utilize all-new art supplies because a patient cannot use what other people have touched,” said Withers. Withers, a Mission District resident, said oil painting is her medium of choice. Yet she sometimes cannot show patients how to engage in this art form because they’re sensitive to smells. At times it’s not easy to get patients to start work. “People feel very vulnerable. They have had intense experiences. I don’t rush people into it. I develop a relationship with patients first,” said Withers. Withers said helping patients tap into their creative and artistic abilities produces “the most amazing and beautiful artwork. Everyone has a story to tell. When they realize their emotions, it’s no wonder that the art that they make is so powerful.” The Potrero View

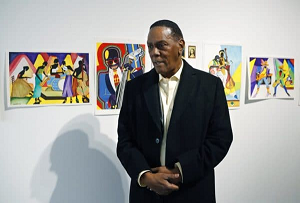

Man Exonerated After 45 Years Sells His Prison Art to Get By: It’s ‘What I Did to Stay Sane’

“I didn’t actually think I’d ever be free again. This art is what I did to stay sane,” the 73-year-old said. Phillips could be eligible for more than $2 million under a Michigan law that compensates the wrongly convicted, but the state so far is resisting and the matter is unsettled. So he’s displaying roughly 50 of his more than 400 watercolors at a Detroit-area gallery and is willing to sell them. His paintings are precious to him, but he said he has no choice: He needs money. Phillips was released from custody in 2017 and, in 2018, became the longest-serving U.S. inmate to win exoneration. He was cleared of a 1971 homicide after an investigation by University of Michigan law students and the Wayne County prosecutor’s office. Phillips is showing his work at an art gallery inside Level One Bank in Ferndale, a Detroit suburb. A reception was planned for Friday night. “Are you the artist? God bless you. Beautiful,” a bank customer said while admiring a painting of five musicians Thursday. Phillips said he bought painting supplies by selling handmade greeting cards to other inmates. He followed a strict routine of painting each morning while his cellmate was elsewhere. He was sometimes inspired by photos in newspapers and liked to use bright colors that didn’t spill into each other. But a cramped cell isn’t an art studio. Phillips said prison rules prevented him from keeping his paintings so he regularly shipped them to a pen pal. After he was exonerated, Phillips rode a bus to New York state last fall to visit the woman. He was pleased to find she still had the paintings. “These are like my children,” Phillips, a former auto worker, said during a tour with The Associated Press. “But I don’t have any money. I don’t have a choice. Without this, I’d have a cup on the corner begging for nickels and dimes. I’m too old to get a job,” he said. Wayne County prosecutor Kym Worthy supports Phillips’ effort to be compensated for his years in prison. Michigan’s new attorney general, Dana Nessel, is reviewing the case. It’s complicated because he has a separate disputed conviction in Oakland County that’s still on the books, spokeswoman Kelly Rossman-McKinney said. Phillips’ attorney, Gabi Silver, who has helped him adjust to a life of freedom, said the paintings are inspirational. “To suffer what he has suffered, to still be able to find good in people and to still be able to see the beauty in life — it’s remarkable,” she said. Atlanta Black Star

How the 300-year-old Kangra school of art is getting a fresh lease of life

Monu Kumar, 37, who works at the gallery, is one of half-a-dozen artists who have been trained by KAPS in the Kangra painting tradition and are currently working as full-time painters. Set up in 2008 by IAS officer BK Agarwal, who was then the divisional commissioner of Kangra and is currently chief secretary to the Himachal Pradesh government, the society was meant to boost what was then a floundering art form. “An art lover himself, he got others, including some well-to-do locals and NRIs, to establish the society with the idea of training artists in this art form,” says Varun Singh, secretary of KAPS. The society’s first move was to run a competition to identify local artists who could be trained in the tradition. The selected artists underwent a year-long course, besides being paid a monthly stipend and provided access to master artists and materials. Kangra painting, like most traditional art forms, demands rigour and discipline. Its characteristic delicate lines on sheets of handmade wasli paper can only be drawn using squirrel hair brushes. The paper and the brush, which were once made by the artists themselves, now have to be brought from Rajasthan. The paper is pressed and primed for days and the paints are ground by hand from raw minerals — also acquired from Rajasthan — in heavy stone pestles. These are processes that go back centuries, and predate the late 17th to early 18th century exodus of artists from the Mughal court and their arrival in the tiny Himalayan states of Guler, Chamba, Nurpur, Kangra, Garhwal and Basohli, where they flourished and created the Pahari school of painting. Kumar says, the techniques and materials remain unchanged. “Most of the time, the subject matters are age-old ones which continue to be favourites among art collectors and patrons,” says Kumar. So just like the painters in the court of Maharaja Sansar Chand Katoch (1776-1824), a Krishna bhakt and one of the patrons of Kangra painting, the artists working with KAPS continue to depict the life and amorous adventures of the blue-hued God, taking episodes from Bhagavata Purana and Jaidev’s Gita Govinda. The artists are also, however, being encouraged to explore other themes. Kumar shows images of a painting depicting the celebration of Rali Mela, which was commissioned by the state government and presented as a gift to President Ram Nath Kovind. “I was inclined towards painting since I was a child. After completing school, I got interested in thangka (Tibetan Buddhist scroll painting) for a while. When I heard about the competition by KAPS, I decided to apply,” says Kumar, who’s been with the society for 10 years. Besides being a full-time artist, he looks after the gallery. Most artists are encouraged to work independently even as they continue to make paintings that are sold by KAPS. “Earlier, when we were giving the artists a monthly stipend, we noticed that the quality was not improving. So we decided to grade the paintings based on quality, and the pricing began to be based on the grade. The grading is done by master artist Mukesh Kumar of the Chamunda Devi Temple,” says Singh. The society still supplies all materials. Every month, when artists submit their works for sale, they receive 40 per cent of the price before sale, with the remaining amount coming through once the painting is sold. “It is important that the paintings sell and that the artists are able to make a living. But this work can’t be sustained by selling paintings. We get commissions from the state government, but we need to look at productizing,” says Singh. The high standards will still be a priority. “Since everything is handmade, it has a certain price range. The Kangra painting has become a symbol of the region. It has a market and we’re playing a small role in ensuring that it expands, ” says Singh. The Indian Express

What's Up South Texas: San Antonio artist wins world record for mini art

“It’s not only painting a wall or a canvas,” said Ochoa. “No, there's art in absolutely everything and we all do it." Ochoa was born and raised in Peru, and has been painting since she was a young child. "It always came natural to me,” Ochoa said. “I love the simple things of the lights. They are pretty. My favorite things to paint are nature and flowers.” She came to the United States 30 years ago, and though English has been an obstacle for her, it hasn’t stopped her love to serve others through her paintings. “I am a professor of fine arts for special education students,” Ochoa said. “Students who have difficulty learning or are struggling with something. I help.” Ochoa said she was inspired by a painter who used grains of rice as his canvas for his paintings. “He showed the collection under a large magnifying glass, which caught my attention, and also motivated me to show my small paintings, that each time were growing in number and you did not need a magnifying glass to appreciate the shapes and colors,” Ochoa said. Over the course of years, Ochoa successfully painting 5,000 miniature paintings. “I have several friends who are artists and they saw my work and said I should fill out an application for the Guinness Book of World Records,” Ochoa said. “So I did and it was a very long process.” There were certain factors Ochoa needed to officially earn the title of a Guinness Book of World Record holder such as a venue to exhibit her art, and each piece needed to be named and framed. She ended up winning the Guinness World Record for the largest collection of miniature paintings in August of 2018. “We think that art is just grabbing a piece of paper to draw or paint,” Ochoa said. “No! We make art everywhere. Setting the table. Fixing up the house. There's art in everything. We all make art, all the time.” In the decades of her artistry, Ochoa has also won several other awards including an eternal rose from the Hispanic-American Cultural Society and recognition from the Department of Homeland Security. No matter the amount of achievements she has had, Martha said her biggest achievement is inspiring others to be their own artists. “My message to the community is for them to persevere in what they like to do. We need to focus on doing this all the time,” Ochoa said. “We all have many many talents. We need to always express them.” Ochoa said her next goal is beat her own record by painting a collection of 10,000 pieces. KSAT

Painting on Location Without Chemicals

An increasing number of plein air artists are taking advantage of water-mixable oils that can be applied as thick as oils, as thin as watercolors, or as varied in levels of opacity of acrylics. Those artists have to learn to handle the unique qualities of the water-mixable paints, and they’ll have to buy a completely new set of colors and mediums, but the outdoor painters appreciate that they no longer have to work with turpentine or mineral spirits and they can manipulate the paint with a wide variety of tools. Even if artists use the solvent-free paints only when traveling or making small studies, they can take full advantage of the medium. Beth Bathe (www.facebook.com/BathePainting) had been painting with traditional oil colors and creating high-chroma figurative and landscape paintings. She then became aware of the work of Vermont artist Charlie Hunter, who champions Cobra brand water-mixable oils, and she took a workshop with Hunter to learn more about the medium and his graphic style of painting. Since switching to water-mixable oils, Bathe has established a procedure of working on Gessobords, birch plywood, or hardboard panels sealed with multiple layers of acrylic gesso that she tints with a small amount of transparent yellow ochre acrylic paint. Those panels range in size from 8 x 16 up to 18 x 24 inches. The exception is that she painted on a 24 x 36-inch panel during the 2017 Plein Air Easton event. Her palette includes Cobra water-mixable raw umber, ultramarine blue, transparent red oxide, titanium white, titanium buff, with secondary colors yellow ochre, cadmium yellow, cadmium red light, permanent green light, violet, grayish blue, and sometimes cadmium orange. Before she begins painting, Bathe coats the surface of her board with a small amount of oil (water-mixable safflower oil) to make it easier to take paint off, even to the point of restoring the white of the substrate. Another technique that helps her lift paint off the panels is to lay a light mist of water over the applied paint using a spray bottle in the same way a watercolorist would to direct paint to flow down a sheet of paper. And if she decides to blot the dripping paint with paper towel, she can add textures that suggest leaves or other natural forms. Because of her strong drawing skills, Bathe doesn’t need to make detailed preliminary drawings before starting to put paint on her panels. “I like what happens when I apply the first washes of diluted color,” says the artist. “I want there to be drips and splashes I can carve into with brushes, Q-tips, paper towels, and other tools. The process of adding and subtracting paint takes me to places where the painting needs to go. The paint takes on a naturalness with its own organic, flowing, dripping qualities. In the end, many finished paintings have the look of tinted photographs because the main image is rendered in warm sepia and enhanced with veils and spots of local color.” Outdoor Painter

‘This Is a Different Kind of Stress’: U.S. Government Shutdown Leaves Many Arts Workers Without Paychecks

To better understand the effects of the shutdown on workers at these institutions, ARTnews spoke to Smithsonian employees about how they are making ends meet without a steady paycheck. Linda Thompson, the Smithsonian Institution’s chief spokesperson, is one of around 800 employees exempt from the furlough. (Many of those employees, she explained, are zoo workers who need to care for animals throughout the shutdown.) “We’re furloughed, but we’re expected to come to work,” she told ARTnews. When everyone receives backpay, Thompson said, she will get the wages she is owed for the time spent working during the shutdown. But some employees have been out of work entirely, and a quarterly tax system has left some contracted Smithsonian Institution workers scrambling to find ways to make ends meet. Nearly a third of the workers at the museum are contractors, meaning that they are not on the institution’s payroll. One such contractor for the institution, who asked not to be named, citing fear of retaliation, told ARTnews that quarterly taxes needed to be paid on January 15, several weeks into the shutdown. “Luckily, I had a solid chunk of money saved up so I could pay my taxes,” the contractor said. But other expenses had caused alarm as well: “I’ve already had to pay my rent since the government closed, and if we go on another week, I’ll have to pay it again. . . . For me, the insecurity isn’t if the money will come through, it’s when it will come through.” Other contractors have been forced to rely on friends and family for the needed funds, she said. Among those that have had to work without pay, as the Washington Post reported last week, are workers at the National Gallery of Art who deinstalled a Rachel Whiteread retrospective. (The shutdown could affect future exhibition programming as well: the NGA may need to delay the start of the first-ever American retrospective devoted to Tintoretto, which is currently set to open in March.) Some employees have confronted politicians about the matter. The Post released a video in which Faye Smith, a security guard at the Hirshhorn, stormed into Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s office, telling him, “If I don’t have my rent by next month I’ll be evicted automatically. I can’t go to my family, Mr. McConnell. My family is with the federal government. Five people in my family are furloughed.” Smith said she had to bring her jewelry to pawn shops to pay bills. To support each other, workers have begun coordinating efforts to make sure their colleagues are financially stable through group texts and other means. “Some of us are good enough friends where we check in with each other on whose paycheck to paycheck and whose not,” the contractor said. “Some people are fine right now, some aren’t.” Another federal employee, who also asked not to be named, told ARTnews that the shutdown had begun to alter their daily routine. “Work is stressful because you have tasks to do on a timeline, but this is a different kind of stress,” the employee said, expressing doubt over when the shutdown will be resolved and back pay issued. “I had a structure to my day that totally went away. . . . Not to mention money—when I’m stressed at work, I know that at least I’ll get a paycheck every two weeks.” The employee said colleagues had started seeking other forms of work in the interim. “There’s been a lot of interesting stuff that’s been going on in D.C. to try and support people during this really crazy time. They’ve been opening up roles for more substitute teachers and things like that, places have been offering discounts, and just more little things to help people out.” Some employees, like the contractor, have continued working remotely, with the hope that their invoices for their labor will paid off at a later date. “I knew that there would be nobody around to process invoices, so I know that I won’t be paid until the government reopens,” the contractor said. “But that’s so much better than the alternative, which is [not] putting in the hours.” ARTNEWS

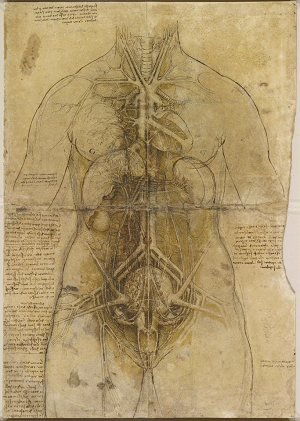

Leonardo da Vinci's thumbprint discovered on drawing in Royal Collection

The sheet with the thumbprint is entitled The Cardiovascular System and Principal Organs of a Woman (around 1509-10). Although fingerprints have been found on other Leonardo drawings, Donnithorne describes the one on the medical sheet as “the most convincing candidate for an authentic Leonardo fingerprint” among the Queen’s 550 or so Leonardos. The medical drawing is to be displayed at the National Museum Cardiff (1 February-6 May) and then at the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace (24 May-13 October). Further details on the discovery will be included in Donnithorne’s new book, Leonardo da Vinci: A Closer Look, to be published on Friday (1 February). The publication of the book coincides with a series of Leonardo displays which will take place with 12 different drawings from the Royal Collection shown simultaneously in 12 venues (Belfast, Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Derby, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Southampton and Sunderland), involving a total of 144 loans. An exhibition of 200 Leonardo drawings will then be assembled at the Queen’s Gallery in London and finally a somewhat smaller show will be at the Queen’s Gallery in Edinburgh (22 November-15 March 2020). The Art Newspaper

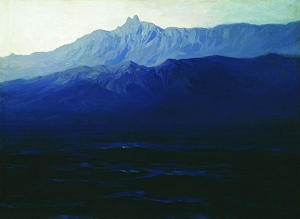

Thief of Crimean painting at State Tretyakov Gallery apprehended

The painting titled Ai-Petri. Crimea (1898-1908), has been on loan to the Tretyakov from St. Petersburg’s State Russian Museum for a retrospective (until 17 February) of works by one of Russia’s most famous landscape artists. It has resulted in long lines and extended hours since it opened in October. The exhibition is running at the Engineering Building annex adjacent to the gallery’s main building. Security camera footage released on Monday shows a totally brazen act. A man who looks like any other visitor walks straight up to the painting, picks it up off the wall, and walks through the exhibition hall with it swinging from his right hand. Only the few people who had been standing immediately next to him look a bit stunned. No one else in the crowd appears to notice, some thinking he was museum staff it was later reported. Irina Volk, a spokeswoman for Russia’s interior ministry said on Monday that a 31-year old man, who had been detained for drugs possession in December 2018 had been caught and that the painting was found at a construction site near Moscow. According to Tass, he could face up to 15 years in prison. On Monday, Olga Golodets, a deputy prime minister who oversees cultural affairs, ordered the ministry of culture to investigate all federally-run museums for security compliance and hold extra training for staff. Russian museums have been complaining of a security shortage since budget cutbacks in 2015. Mikhail Piotrovsky, the director of the State Hermitage Museum, lobbied for reinforcements from Rosgvardia, a national guard service created by President Vladimir Putin. A Rosgvardia official said on Sunday that the agency’s staff only man the entrance of the Tretyakov’s Engineering Building. In May 2018, a visitor to the museum’s main building vandalised a painting by Ilya Repin, Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan (1885) with a metal security pole. Police are currently also investigating a report of a 16th-century icon missing from the storage of the State Historical Museum. Zelfira Tregulova, the general director of the Tretyakov Gallery, said at a news conference on Monday that the Kuindzhi painting, which does not appear to have been damaged, would not return to the exhibition. A culture ministry official said it had been insured for 12m rubles, but denied media reports that it was worth $1m at auction, saying that a museum piece cannot have an estimated auction price. A Kuindzhi painting sold for over $3m at Sotheby’s in 2008. Since the Ai-Petri depicts a mountain peak in Crimea, Facebook users compared the theft to Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Many also joked about similarities to a tragicomic Soviet film about two elderly men who steal a Rembrandt from a museum. Others suggested that the Tretyakov was spending too much time cracking down on unauthorised museum tours that have reportedly led to some people who were simply talking to each other about paintings from being kicked out of the museum, rather than guarding its treasures. The Art Newspaper

How Letraset Transformed Graphic Design

Presented at first as an alternative to hand lettering, dry transfer letterforms stood, for a brief moment, at the intersection of crafts and technology. Easy to use, the method nonetheless required some dexterity. Words had to be set carefully, one letter at a time, and rubbed down in perfect alignment. When done correctly, it could replace traditional typesetting. Anyone could feel the rush of composing elegant headlines within minutes. For a graphic designer in the 1970s, holding a brand-new polyester sheet of 24 point Helvetica Medium Condensed, its neat rows of caps and lower cases ready to be applied on a clean surface, was pure ecstasy. Letraset, a UK company specialising in art supplies, was the main provider of these handy alphabets, which were ubiquitous in design studios worldwide because they could be used to create high-quality camera-ready artwork. Even though setting headlines with these decals required a sure hand and a keen understanding of typographical rules (once the letters were down you could not move them), the result could be stunning: depending on how much pressure you had applied, the words or sentences could look letterpressed or silkscreened. The idea of transferring motifs from one surface to another used to be called ‘decalcomania’. It was popular in the nineteenth century for pressing decorative patterns on to everything from plates to guitars. The Surrealists used the same word to describe a way of applying uneven pressure on a thin layer of gouache to give it a mysterious looking texture. In the 1950s, ready-to transfer cartoon characters were popular with children. But kids had trouble mastering the delicate process, involving sliding the wet images off their transparent backing onto a page, resulting in crumpled figures so bizarre they inspired the term ‘cockamamie’, a deformation of ‘decalcomania’. Decals today are peel-off designs, their sticky backing formulated to bond permanently with anything from automotive parts, model aeroplanes and surfboards to mobile phones, computer cases, furniture and walls. Letraset is no longer known for its innovative transfer letters – the company went back to its craft roots, selling such products as self-sticking adhesive film and metallic ink markers. Cockamamie is not dead, though. Wallpaper manufacturers are now proposing lines of mural-size rubdowns that reproduce eccentric or quirky patterns designed by artists whose sensibility is steeped in comic book culture. Domestic, a French company, publishes wall stickers by avant-garde European graphic designers such as Antoine+Manuel, Marti Guixé, Geneviève Glaucker and Ich&Kar. Digital Arts

Man’s side gig making Star Wars figures eases fears of another shutdown

Mateos, who is a contractor for the US State Department, won't receive any back pay for those 35 days. With the uncertainty of what lies ahead and the possibility of another shutdown, the father is finding new ways to bring in money. His basement has now become his new office. There, he's replicating vehicles from the world’s most famous film series: Star Wars. "Star Wars, it's been in my blood ever since the beginning,” he says. Mateos buys the licensed figures and paints them. "Then, I add the thinner and it becomes a subtractive process,” Mateos explains of his work. So far, he's made a couple thousand dollars by selling them online. But lately, he says it’s not just about the money. “When I do something with my hands and I’m creating something, I don't focus and dwell on all the political stuff that's happening on the Hill,” Mateos says. Mateos looks at this new side hustle as a plan for the future. “The biggest lesson I’ve learned is always be prepared, always have a backup plan, even if things are going really, really well,” he says. WPTV

New watercolour database could help experts combat climate change

The project aims to change preconceptions about the medium which has fallen out of fashion, unearthing examples hidden away in “darkened museum vaults”, says Fred Hohler, the project founder. The initiative is funded entirely by the London-based charity, the Marandi Foundation, which is run by the UK philanthropists Javad and Narmina Marandi. “The current running budget is around £300,000 to £400,000,” Hohler says. Professor Robin McInnes of the Coastal and Geotechnical Services consultancy has drawn on the database to monitor the evolution of the British coast since the late 18th century. An image from the Dorset County Museum, for instance, outlines the changing rock formations near Bat’s Head in Lulworth. McInnes’s findings are due to be published in May (The State of the British Coast; observable changes through imagery 1770-present day). Some images meanwhile show glacial retreat in the Alps including Glacier de la Côte, Mont Blanc France (around 1800); others depict rare examples of flora and fauna. Between 1750 and 1900, watercolour production snowballed. Eighteenth-century artists such as Thomas Sandby, who specialised in military images working for the Duke of Cumberland, elevated the medium while paintboxes, pioneered by companies such as Reeves & Co of London, meant that artists could work outside. “You could put it in your pocket and leave the studio. People began recording what they saw, as the old agricultural states were transformed during the Industrial Revolution,” says Hohler. In 1900 however, the advent of photography put paid to the watercolour boom. Hohler adds that “we could lose our vision of the period 1750 to 1900 which would be utterly irreplaceable. [Watercolours] are increasingly being lost. If you go round skips, you’ll see!” The Art Newspaper

|

When Frida Kahlo packed for her first trip to the United States, in 1930, she put lots of long skirts in her suitcase. Floor-length skirts had already become the painter’s bohemian uniform by age 23, as she prepared to go to San Francisco with her new husband, muralist Diego Rivera. The colorful garments illustrated her proud Mexican identity while serving a very practical function, too. As a child, Kahlo contracted polio that made her right leg shorter and skinnier than her left; the skirts hid the deformity, with flair.

When Frida Kahlo packed for her first trip to the United States, in 1930, she put lots of long skirts in her suitcase. Floor-length skirts had already become the painter’s bohemian uniform by age 23, as she prepared to go to San Francisco with her new husband, muralist Diego Rivera. The colorful garments illustrated her proud Mexican identity while serving a very practical function, too. As a child, Kahlo contracted polio that made her right leg shorter and skinnier than her left; the skirts hid the deformity, with flair. The city of Norfolk, Virginia, may become one of the first cities in the US to be claimed by rising seas brought on by climate change. Over the past decade, residents of the east-coast naval city have seen a steady uptick in hurricanes and flooding from high tides, wind surges that drive seawater ashore, and overflowing storm drains. Yet, based on the recently released National Climate Assessment report by the US government, coastal cities in the south east—including Norfolk—are not ready to cope with rising sea levels.

The city of Norfolk, Virginia, may become one of the first cities in the US to be claimed by rising seas brought on by climate change. Over the past decade, residents of the east-coast naval city have seen a steady uptick in hurricanes and flooding from high tides, wind surges that drive seawater ashore, and overflowing storm drains. Yet, based on the recently released National Climate Assessment report by the US government, coastal cities in the south east—including Norfolk—are not ready to cope with rising sea levels. The first-ever scientific study of the oldest known drawing by Leonardo da Vinci has found that he added details to an earlier sketch of a countryside landscape, said the Uffizi Galleries, whose collections include the fragile work.

The first-ever scientific study of the oldest known drawing by Leonardo da Vinci has found that he added details to an earlier sketch of a countryside landscape, said the Uffizi Galleries, whose collections include the fragile work. Since 1988, University of California, San Francisco’s Art for Recovery, an art-making, writing, and music program for adults living with cancer, has helped thousands of patients build confidence in themselves and work toward mental wellness. The series is open to anyone dealing with cancer; participants don’t have to be UCSF patients or even under care for a significant health issue.

Since 1988, University of California, San Francisco’s Art for Recovery, an art-making, writing, and music program for adults living with cancer, has helped thousands of patients build confidence in themselves and work toward mental wellness. The series is open to anyone dealing with cancer; participants don’t have to be UCSF patients or even under care for a significant health issue. Richard Phillips said he didn’t mope much during the 45 years he wrongfully spent in prison. He painted watercolors in his cell: warm landscapes, portraits of famous people like Mother Teresa, vases of flowers, a bassist playing jazz.

Richard Phillips said he didn’t mope much during the 45 years he wrongfully spent in prison. He painted watercolors in his cell: warm landscapes, portraits of famous people like Mother Teresa, vases of flowers, a bassist playing jazz. In McLeodganj, along the road from the main square to the Dalai Lama temple are souvenir shops and trinket stalls. There may once have been a time when these businesses sold tchotchkes that were unique to the region, but, over the years, most of their wares have acquired a pan-national character. The macrame wall hangings, papier-mâché boxes, chunky jewellery and cheap T-shirts you find on the streets of McLeodganj, are as much at home here as they are on the pavements along Colaba Causeway or the Wednesday flea market near Anjuna beach. In the chaos of modern commerce, objects harking back to centuries-old tradition can be hard to sell, and yet, this is precisely the task that the Kangra Arts Promotion Society (KAPS), an NGO, has been quietly working at for the last decade. On the walls of its gallery in McLeodganj, an airy space with windows offering stunning views of the valley below, are exquisite paintings in the 300-year-old Kangra painting tradition.

In McLeodganj, along the road from the main square to the Dalai Lama temple are souvenir shops and trinket stalls. There may once have been a time when these businesses sold tchotchkes that were unique to the region, but, over the years, most of their wares have acquired a pan-national character. The macrame wall hangings, papier-mâché boxes, chunky jewellery and cheap T-shirts you find on the streets of McLeodganj, are as much at home here as they are on the pavements along Colaba Causeway or the Wednesday flea market near Anjuna beach. In the chaos of modern commerce, objects harking back to centuries-old tradition can be hard to sell, and yet, this is precisely the task that the Kangra Arts Promotion Society (KAPS), an NGO, has been quietly working at for the last decade. On the walls of its gallery in McLeodganj, an airy space with windows offering stunning views of the valley below, are exquisite paintings in the 300-year-old Kangra painting tradition. Miniature paintings got one San Antonio woman enormous recognition with the Guinness Book of World Records. Martha Ochoa began painting tiny art after having a life’s experience of painting many pieces.

Miniature paintings got one San Antonio woman enormous recognition with the Guinness Book of World Records. Martha Ochoa began painting tiny art after having a life’s experience of painting many pieces. Pennsylvania artist Beth Bathe is featured in the March 2018 issue of PleinAir. Here’s a preview of how she uses water-mixable oils, which have some of the characteristics of oils, acrylics, and watercolors. You may want to use these paints and avoid some chemicals.

Pennsylvania artist Beth Bathe is featured in the March 2018 issue of PleinAir. Here’s a preview of how she uses water-mixable oils, which have some of the characteristics of oils, acrylics, and watercolors. You may want to use these paints and avoid some chemicals. The longest government shutdown in U.S. history has forced arts museums in Washington, D.C.—and beyond—to close for extended periods of time. The Smithsonian museums, including the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden and the National Portrait Gallery, and the National Gallery of Art are among those that have been forced to shutter this month, with some exhibitions at these institutions going off view without any visitors during their final days. But museum employees have been forced to bear the brunt of the shutdown as well.

The longest government shutdown in U.S. history has forced arts museums in Washington, D.C.—and beyond—to close for extended periods of time. The Smithsonian museums, including the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden and the National Portrait Gallery, and the National Gallery of Art are among those that have been forced to shutter this month, with some exhibitions at these institutions going off view without any visitors during their final days. But museum employees have been forced to bear the brunt of the shutdown as well. A Leonardo thumbprint has been discovered on one of his works in Britain’s Royal Collection. The mark, from his left thumb (the artist was left-handed), is on a medical drawing. Alan Donnithorne, the collection’s former paper conservator, found that the reddish-brown ink of the print is the same as that on the drawing, so Leonardo presumably “picked up the sheet with inky fingers”. There is also a smudged mark of his left index finger on the reverse.

A Leonardo thumbprint has been discovered on one of his works in Britain’s Royal Collection. The mark, from his left thumb (the artist was left-handed), is on a medical drawing. Alan Donnithorne, the collection’s former paper conservator, found that the reddish-brown ink of the print is the same as that on the drawing, so Leonardo presumably “picked up the sheet with inky fingers”. There is also a smudged mark of his left index finger on the reverse. A man who grabbed a valuable late 19th- early 20th-century scene of Crimea by the artist Arkhip Kuindzhi off a wall at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow on Sunday evening in full view of visitors and personnel, has been apprehended and the painting recovered. But the incident has raised serious questions about museum security in Russia and has inspired a slew of ironic memes.

A man who grabbed a valuable late 19th- early 20th-century scene of Crimea by the artist Arkhip Kuindzhi off a wall at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow on Sunday evening in full view of visitors and personnel, has been apprehended and the painting recovered. But the incident has raised serious questions about museum security in Russia and has inspired a slew of ironic memes. In an age before computers made layout almost effortless, Letraset revolutionised typesetting – letting designers create headlines in mere minutes. In this extract from Lawrence King's updated edition of 100 Ideas That Changed Graphic Design by Steven Heller and Véronique Vienne, the authors chart the decades when a British company's rub-on lettering (and its knock-offs) were ubiquitous in every design and advertising agency in the UK, Europe, the US and beyond.

In an age before computers made layout almost effortless, Letraset revolutionised typesetting – letting designers create headlines in mere minutes. In this extract from Lawrence King's updated edition of 100 Ideas That Changed Graphic Design by Steven Heller and Véronique Vienne, the authors chart the decades when a British company's rub-on lettering (and its knock-offs) were ubiquitous in every design and advertising agency in the UK, Europe, the US and beyond. For 35 days during the partial government shutdown, Michael Mateos took on the role of stay-at-home dad.

For 35 days during the partial government shutdown, Michael Mateos took on the role of stay-at-home dad. A new online database of watercolours painted before 1900 will help scientists and environmentalists combat climate change, say the project representatives. Watercolour World, which went live earlier this week, currently comprises around 80,000 images drawn from private and public collections worldwide; users can search according to place or subject. “The project uses an overlooked artform to help reveal the world as it looked before photography,” say the organisers.

A new online database of watercolours painted before 1900 will help scientists and environmentalists combat climate change, say the project representatives. Watercolour World, which went live earlier this week, currently comprises around 80,000 images drawn from private and public collections worldwide; users can search according to place or subject. “The project uses an overlooked artform to help reveal the world as it looked before photography,” say the organisers.